The Rijndael block cipher first creates a key from the key schedule, runs an initial round, and then starts its main rounds. There are four steps of the main rounds: 1) SubBytes, 2) ShiftRows, 3) MixColumns, and 4) AddRoundKey. One defining aspect of the Rijndael cipher is that it takes place inside a Galois field defined as GF(28). This plays a key part in the SubBytes and the MixColumns step. Another defining aspect is that the first step is to change the 128-bit plain text into a binary, and then to put it in a 4×4 matrix. This 4×4 matrix is called the state and it is what all future steps operate on. Each byte in the 4×4 matrix is composed of 8 bits and represents one character. The first step, SubBytes is the substitution part of the cipher, and the second and third steps, ShiftRows and MixColumns, are the permutation parts of the cipher.

128-bit example text: The cat flew!!!!

Convert to binary: 01010100 01101000 01100101 00100000 01100011 01100001 01110100 00100000 01100110 01101100 01100101 01110111 00100001 00100001 00100001 00100001

Put in a 4×4 state:

| 01010100 | 01100011 | 01100110 | 00100001 |

| 01101000 | 01100001 | 01101100 | 00100001 |

| 01100101 | 01110100 | 01100101 | 00100001 |

| 00100000 | 00100000 | 01110111 | 00100001 |

A Galois field is a finite field where addition, subtraction, multiplication, or division can be performed on the elements. What makes it finite is that whenever a result greater than 28, (or 256) is achieved, the modulus operation is applied, and the result instead wraps back around to the beginning of the field. This keeps all the results inside the field and is crucial to the Rijndael S-box that is used in the first step, SubBytes.

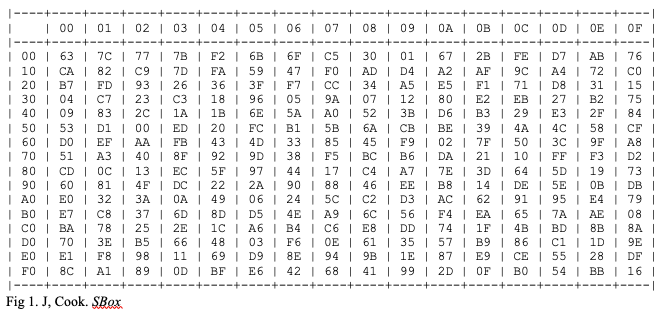

AES S-box

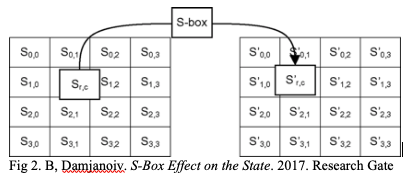

The math required to map a value to its corresponding S-box value is quite complicated and is one reason the Rijndael cipher is so strong. The polynomial used in Rijndael’s Galois field is x8+x4+x3+x+1, and the S-box value is mapped based on first the multiplicative inverse over the Galois field, and then by using an affine transformation. The SubBytes step maps each corresponding byte to a value in the S-box. On the S-box, the columns are determined by the least and most significant nibbles of the byte, converted into hexadecimal form. The result of this step is that the original sixteen bytes in the 128bit block have been mathematically manipulated to another of 4×4 table of practically untraceable bytes.

Fig 2. B, Damjanoiv. S-Box Effect on the State. 2017. Research Gate

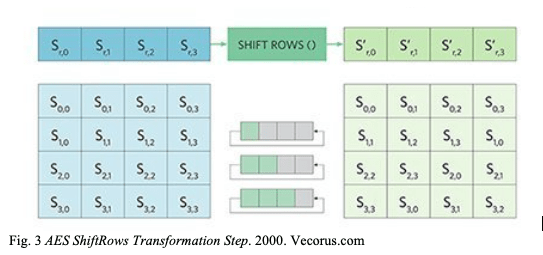

The next step, ShiftRows, is the simplest step in the round. The first row is not shifted, but the second row is shifted left by one, the third row is shifted left by 2, and the fourth row is shifted left by three. This adds the first layer of permutation.

Fig. 3 AES ShiftRows Transformation Step. 2000. Vecorus.com

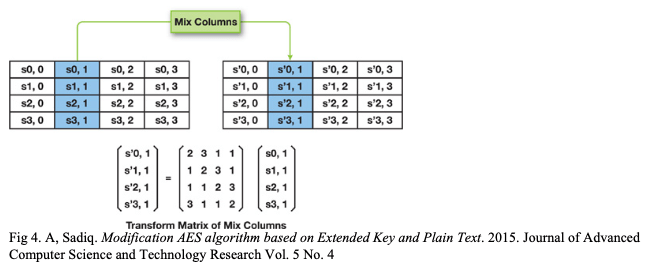

The third step, MixColumns, adds the second layer of permutation. Each column is multiplied by a fixed matrix (inside the Galois field) to produce a new byte. The specific math of the matrix multiplication is that each column is treated as a polynomial in the form and then multiplied with the fixed polynomial

mod

.

Fig 4. A, Sadiq. Modification AES algorithm based on Extended Key and Plain Text. 2015. Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Technology Research Vol. 5 No. 4

The last step of the round AddRoundKey is to XOR the resultant 4×4 state block bitwise with the round-specific subkey determined by the key schedule, which produces the final encrypted state of the 128-bit block.

These steps are repeated either 10, 12, or 14 times depending on the length of the key. In the last round, the MixColumns step is omitted. Although the Rijndael cipher uses very complicated math to produce the cipher text, each step has a mathematical inverse that makes decrypting (with the proper key) a swift feat.

Daemen, J., & Rijmen, V. (1999, September 3). AES Proposal: Rijndael. Retrieved December 5, 2019, from https://csrc.nist.gov/csrc/media/projects/cryptographic-standards-and-guidelines/documents/aes-development/rijndael-ammended.pdf.

Easttom, C. (2016). Modern Cryptography. McGrawHill Education.

Pound, M. (2019, November 22). AES Explained – Computerphile. Retrieved December 5, 2019, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O4xNJsjtN6E.